Workers sink concrete blocks into waters off Qinhuangdao, Hebei province, to build artificial reefs that industry insiders say will attract large numbers of fish and restore the damaged marine environment.[Photo by Liu Xuezhong/China Daily]

Sun Xianli used to make a good living from the sea, but since 2011 his income has fallen dramatically as a result of pollution and overexploitation of fish stocks. In 2012, Sun’s crop of mussels at his “sea ranch” failed, and he lost his main source of revenue.

“Too many people were farming the sea, and the water was filthy because construction sites on the coast were discharging industrial sewage into the water day and night,” said the 50-year-old from the coastal city of Rizhao in Shandong province.

A fisherman carries produce at a port in Lianyungang, Jiangsu province. Local fishing resources have recovered in recent years thanks to artificial reefs and other measures for marine environment protection.[Photo by Si Wei/China Daily]

In 2013, a desperate Sun used a local government subsidy to sink concrete blocks in the shallow coastal waters to create a sustainable habitat for marine creatures that would attract large numbers of fish.

“The government launched a project to build an artificial reef in 2013. They told me the blocks would become a new home for the fish and restore the damaged environment,” he said. “Now, the reef is my only hope.”

Artificial reefs, which are used extensively in the United States and Japan, were first introduced in China in the 1980s, but have only been built in large numbers in recent years. The continuing deterioration of the underwater environment in coastal areas has resulted in the structures increasingly being used to promote marine life and fishing, and the scale in China is rapidly approaching those of Japan and the US, according to the State Oceanic Administration.

“Fish gather around reefs. That’s common knowledge among fishermen,” Sun said. “In 2008, we caught fish worth 300,000 yuan ($48,000) in the waters near a 10-meter-long shipwreck, so I believe our artificial reef will attract a lot of fish.”

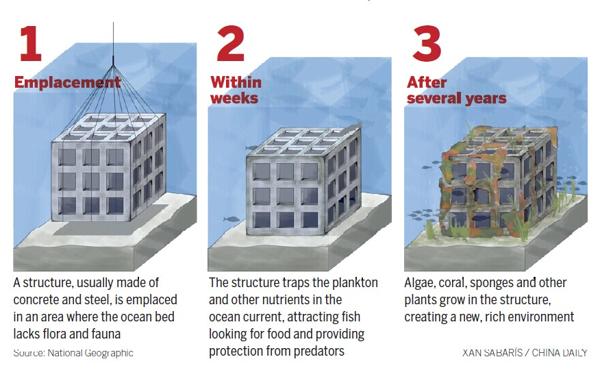

The Rizhao government has built six large artificial reefs, using concrete blocks, tubes and rocks. The largest covers 98 hectares and includes more than 100,000 concrete blocks, each of 1 cubic meter. By providing hard surfaces to which algae and invertebrates such as barnacles and coral can attach themselves, artificial reefs attract large numbers of marine creatures and provide homes and food for fish.

[Design/China Daily]

“Artificial reefs attract fish, which breed in the waters around them and boost the population. That allows us to reduce the scale of sea farming and the pollution it causes. It also means we can reduce the scale of long-range fishing to protect marine life in the deep oceans,” said Zhu Jingyou, deputy director of the Rizhao Oceanic and Fishing Administration. “The development of artificial reefs will be an important part of our job in the coming years.”

Although artificial reefs were first used in Japan to boost fish stocks and marine agriculture after World War II, a similar practice had been employed on a very small scale in certain parts of China for centuries.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), fishermen in the coastal areas of southern China embedded bamboo poles in the sea bed and filled the spaces between them with rocks and tree branches to create environments that would attract fish.

An important role

In the 1980s, Shandong and Guangdong provinces undertook a number of reef pilot projects, but a lack of investment meant the scale was too small to be profitable or benefit the local fishing industry, according to Liang Zhenlin, director of the School of Marine Biology at Shandong University.

“Now, artificial reefs have spread along the coastline, from the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region in the south to Liaoning province in the north. They play an important role in the rejuvenation of the underwater environment and replenishing the fish population,” he added.

The function of the reefs varies according to location: Those in southern China are mainly used to promote environmental conservation efforts, while those in the north of the country are used in the production of high-end marine produce, including sea cucumbers and abalone, both of which are firmly in the luxury food bracket.

The country’s vast 18,000-km coastline and the large expanse of water are advantageous for the development of artificial reefs, and could see China’s system quickly outstrip those in Japan and the US, meaning that both the environment and the fishing industry could benefit over a shorter time scale.

In 2013, Dongtou, an island county in Zhejiang province, spent 230 million yuan on the construction of the country’s largest artificial reef, dubbed the “ocean ranch”, composed of 90,000 cubic meters of concrete blocks across 150 hectares of ocean, which has produced a marine-life propagation area of more than 1,000 hectares.

“If we don’t start building more reefs now, it will be too late,” said Lin Shaozhen, senior engineer at the Zhejiang Marine Culture Research Institute.

According to a 2014 report released by the State Oceanic Administration, China’s fishery resources have declined rapidly in recent decades, especially bell fish and large yellow croakers. Some other species have simply vanished, and the proportion of high-end fish in the total annual catch fell to 30 percent from 50 percent in the 1960s.

“We are not only building reefs, but also cultivating and releasing various fish fry,” Lin said, as she stood in a greenhouse-type structure that housed pools stocked with 40-day-old large yellow croakers that will be transferred soon to “sea ranches” and reach adulthood in six months. Lin said the reef will provide a natural habitat for the fry, which means their diet will be entirely natural and unaffected by human food waste.

Despite the acceleration in their development, the artificial reefs need to be regulated to ensure that they are effective and environmentally friendly, and their location and standards should be carefully assessed to prevent damage to the fragile maritime ecosystem, Lin said.

“More important, the restoration of the maritime environment requires a systematic approach that focuses on controlling pollution, preventing overfishing, and safeguarding the future for coastal people.”