Researchers dressed as pandas conduct a checkup on a cub at the Hetaoping reintroduction base in Sichuan province.[Photo/China Daily]

China plans to build a Giant Panda National Park spanning three provinces to help the endangered animals mingle and enrich their gene pool.

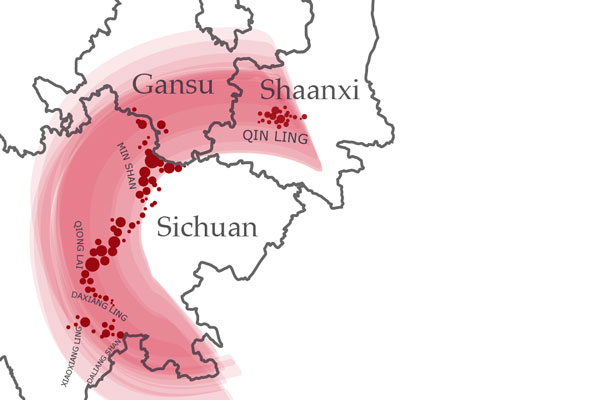

Pandas isolated on six mountains in the provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi and Sichuan will be able to come together in the proposed park, which will cover 27,134 square kilometers, three times the area of Yellowstone National Park in the United States.

It will have a core area, protecting pandas in 67 existing reserves as well as another 8,000 endangered animals and plants.

Like many endangered species, pandas are suffering loss and fragmentation of their habitat as a result of natural disasters, climate change and expanding human activity.

The problem is exacerbated by the multiple administrations controlling the three provinces, because jurisdiction becomes blurred when pandas cross provincial boundaries.

The park will solve the problem. When it is complete, the pandas will be able to roam freely between their far-flung habitats. It will also lead to the relocation of a lot of people-for example, at least 170,000 people in Sichuan will have to relocate to establish the core protection area.

“Unlike nature reserves, the park will not stand alone. China will formulate an overall plan for the national park system. It will be a haven of biodiversity and will provide protection for the whole ecological system,” said Hou Rong, director of the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding in Sichuan.

According to the plan, China’s national park system will comprise the Giant Panda National Park and eight other facilities devoted to endangered species and the headwaters of major rivers. Last year, the central government endorsed reform plans to “advance ecological progress”, which included the plan to establish national parks.

Hou said the park will offer residents new homes and jobs. Many could be employed as tourist guides and as construction workers on infrastructure projects, so people and nature will benefit together.

People have lived in panda reserves for generations, but they cut bamboo shoots and grazed their livestock on hills, eating into the pandas’ habitat and disrupting their lives.

Qubie Mazi, a member of the Yi ethnic group, has lived in Sichuan’s Hei Hezi village for 40 years, making a living by growing potatoes and collecting herbs. A panda reserve in the village is a key corridor connecting populations on nearby Liangshan Mountain.

Poverty once drove the villagers to poach pandas, but after a penalty-and-bonus system was introduced, they learned to value the national treasures and now cherish them.

“I saw a panda in one of the village houses a month ago. I guess he came to look for food or company. I know that when they need to mate, they go to the other side of the mountain. When I discover something unusual about the pandas, I report it to the reserve,” Qubie said.

Asked how he feels about making way for pandas, he said, “I will move, providing I can have a new home and a new job.”

According to Heng Yi, a senior member of staff at the China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda, higher living standards would benefit both the local population and the pandas.

“We should lead the locals to protect the environment, not spoil it. The key measure is to help people live sustainable lives and to get them out of poverty. Once they have access to electricity, they will stop cutting down bamboo. If they have decent jobs and steady incomes, they won’t risk poaching pandas,” he said.

Return to the wild

Hou said the national park plan has had to address significant economic and practical challenges because Panda-conservation work has three major stages: breeding; reintroduction to the wild; and the national park.

“We had to start captive-breeding programs in the late 1990s because panda numbers fell dramatically in the 1980s, partly because of a periodic natural die-off of bamboo,” he said.

Scientists worked to breed the reclusive animal in captivity, overcoming a number of early failures. Last year, 64 cubs were born, and 54 of them now live in nature reserves and zoos, according to the State Forestry Administration.

Scientists are also troubled by the pandas’ inbreeding. For many years, they worked with international research teams to make pandas one of the most genetically diverse animals in captivity.

To enrich the gene pool, the conservation and research center started the reintroduction program in 2003. It reintroduced seven pandas into the wild, but two died.

Keeping the animals behind bars is the last thing Zhang Hemin, the center’s deputy director, wants. “The goal of breeding and reintroduction is to eventually put the animals back into bamboo forests and expect them to mate with their wild cousins,” he said.

Thanks to the center’s conservation efforts, 1,864 pandas remain in the wild, a rise of 17 percent from a decade ago, according to the most recent national survey, conducted in February 2015.

The aim is to raise the wild population to more than 2,000 by 2025, which will require a large protection area and an upgraded ecosystem. “That’s why many scientists and conservation experts support the building of a national park,” said Hou, who proposed the idea in 2014.

Few people are aware of how pandas live in the wild, he added. Much of their range is fragmented, and only a few large continuous tracts remain where the animals can roam freely.

According to a report by the World Wildlife Fund, roads and railroads are increasingly fragmenting the forest, which further isolates panda populations and prevents them from mating, while the destruction of forests reduces their access to the bamboo they need to survive.

Some sub-populations number fewer than 10 members, making them vulnerable to disease and reproductive problems, and less able to adapt to a changing environment.

Challenges

While the park paints an encouraging picture of panda conservation and the restoration of the ecological system, it also faces challenges and risks.

Restoring effective corridors for panda migration is no easy task. Twenty plans for corridors across the six mountains have been proposed since 1988, but few have come to fruition.

“China still needs to conduct more empirical studies and to carry out conservation activities to put these corridors into real use,” said Melissa Songer, a conservation biologist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park in Washington.

In 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission and the Paulson Institute in Chicago signed a cooperation framework protocol to conduct pilot programs and case studies.

“Past experience has shown us how much a national park can do for a country’s environment and ecology,” said David Wildt, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute.

“I am delighted to see China’s breakthrough in panda breeding-and-reintroduction programs. But it’s time to test if these measures work out in the new system of national parks.”

A female panda teaches her cub to climb a tree at a research center in Sichuan.[Photo/China Daily]

The proposed scale of Giant Panda National Park. The dark-red spots indicate the animals’ fragmented habitats.[Photo/Xinhua]