The government of Beijing is set to consider proposals to boost the number of cyclists on the city’s roads and impose a congestion charge to slash the number of cars.

In 2001, when Ines Brunn first visited Beijing, she was impressed by the sight of millions of cyclists riding along wide, flat asphalt lanes separated from the sidewalks and main roads. The city’s streets abounded with bikes, and during her short stay Brunn was thrilled to see so many cyclists in one place, so she decided to return.

However, in 2006, when she moved to Beijing to live and work, she discovered that the roads had been taken over by automobiles, and the number of cyclists had plummeted.

Her disappointment was compounded by the attitudes of her Chinese colleagues at a multinational company when she told them she cycled to the office every day.

“In their eyes, if you rode a bike you were really poor,” Brunn said, recalling that she had already started working with a number of environmental NGOs to advocate the increased use of bikes. Since then, Brunn-who owns Natooke, China’s first fixed-gear bike workshop, in Wudaoying near the famous Lama Temple-has spent much of her working and leisure time attempting to convince people that cycling is cool, socially responsible, and definitely not an indication of financial status.

“People were listening, but they didn’t want to change. I realized the discussions were not changing people’s attitudes toward bicycles,” said the 39-year-old native of Iserlohn, a city in western Germany.

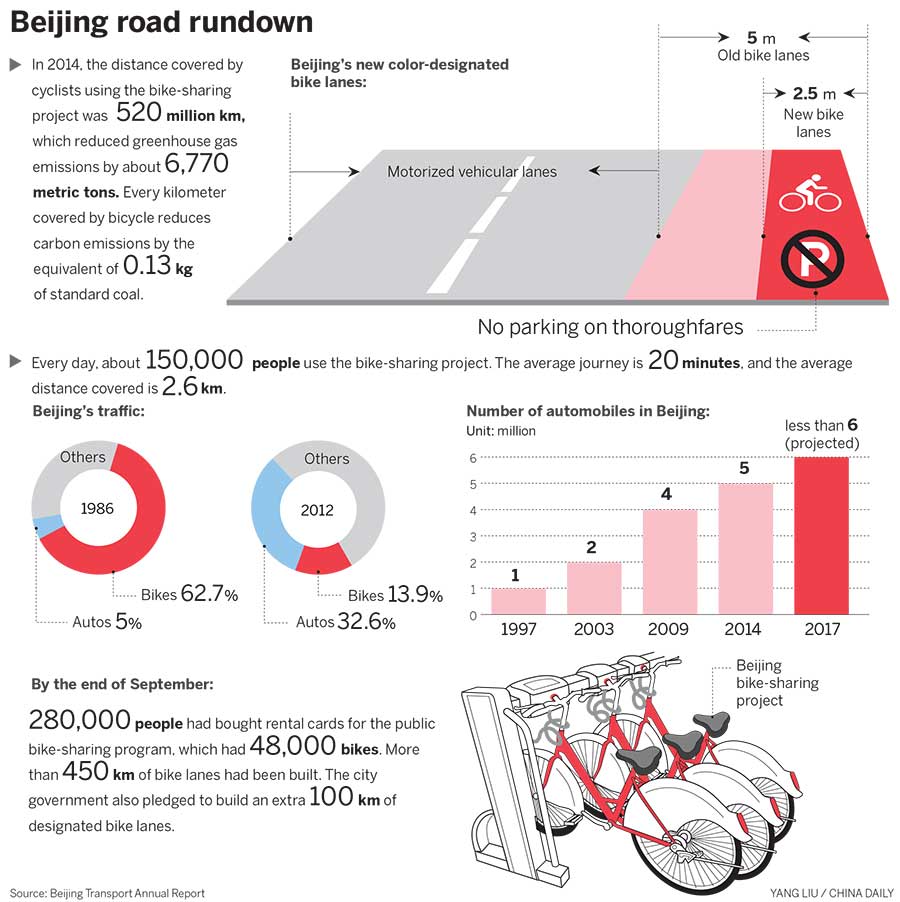

If people weren’t listening to her back in 2006, they are certainly getting the message now, as the city is plagued by seemingly endless traffic jams and declining air quality. In response, as part of a series of “green transportation” measures, the Beijing government aims to make bikes account for 18 percent of the city’s traffic by the end of 2020.

Expanding the focus

Targeting traffic congestion and air pollution, Beijing has planned a raft of policies to make the city a more livable place, and to provide a more sustainable mobility system.

This year, the city government will consider a proposal to trial a congestion charge in the capital, and although no details, such as cost or scope, have yet been announced, experts said the move could be regarded as the fulfillment of one of 28 measures, initiated in 2010 and reaffirmed in 2013, to curb traffic congestion.

In terms of traffic gridlock, Beijing is second only to the southwestern municipality of Chongqing, according to TomTom, a manufacturer of travel software. By the end of August, there were 5.58 million automobiles on the capital’s roads, and the city had 9.65 million registered drivers, almost half the registered residential population.

Every day, traffic congestion accounts for 50 percent of the time spent commuting during the rush hours. Last year, a survey by the National School of Development at Peking University found that the economic loss caused by congestion was about 70 billion yuan ($11 billion), and 80 percent of that was the result of wasted time.

Since 2011, the city has spent 470 million yuan attempting to reduce urban congestion, but some critics say a change of focus is needed.

“It’s time for a full-scale renewal of Beijing’s entire urban transportation system,” said Liu Daizong, China transport program director at the World Resources Institute, an independent, nonprofit organization that provides strategic management for sustainable cities and transportation.

“We can’t continue to build more roads to manage the congestion problem. The more roads we build, the more drivers will aspire to use those roads,” he said. “This should be changed to rebalance the benefits of the roads. We need a distribution-oriented method of managing congestion.”

Competition for road resources between different vehicles is fierce, and experts say an efficient strategy is needed to encourage greener modes of transportation. The greater use of bikes has been heavily promoted since 2011, when the local government began trials of a cycle-sharing project and started advocating the Bus-Metro-Walk strategy.

Since the early pilot projects in two districts of Beijing, the program has grown and 800 rental stands with more than 48,000 bikes now dot the city, said Wang Jiachuan, associate director of the Beijing Transportation Information Center, who added that by the end of last year, the existing 454 km of designated bike lanes had been extended by 100 kilometers.

Cycle-sharing is about more than just transportation, according to Kim Lua, senior associate at World Resources Institute China Sustainable Cities, who said bikes are city friendly because their use results in fewer, and less serious, accidents and they don’t cause pollution. “Promoting cycling as a transportation option can reduce the economic cost to the city. Using well-designed bicycle lanes to improve traffic safety could reduce the human cost,” he said.

Beijing’s road in 1982.[Photo by Wang Wenlan/China Daily]

Obstacles to change

Wim van Wijk from Royal HaskoningDHV, an engineering consultancy in the Netherlands, said that although the intentions are good, there are still many obstacles to be overcome before Beijing can achieve its green transportation goals. Speaking at a seminar at the Dutch embassy in Beijing, Van Wijk said the government must ensure the city infrastructure is designed to encourage a transportation revolution.

The situation in Beijing is reminiscent of those in a number of European cities many years ago: cars squeeze into limited space on narrow lanes intended for cyclists, swamping the old central part of the city during rush hours. At other times, the bike lanes become free parking lots for car owners, whose numbers soar every year.

In the 1970s, every Chinese family aspired to own four things: a sewing machine, a radio, a wristwatch and a bicycle, the ultimate symbol of prosperity in those days. In 1986, the city’s cycling heyday, about 6.3 million Beijingers used bicycles, but by 2013 the number had fallen to 3 million, according to the China National Statistic Yearbook.

From 1990 to 2010, automobile ownership in China skyrocketed from 5.5 million to more than 70 million, and cars began swamping the streets. Municipal government data show that the average speed of traffic on the city’s roads has fallen steadily over the years, and now stands at about 15 km an hour.

“The most efficient way of reducing the number of automobiles is to promote alternative transportation and limit the space available to drivers. That’s the reason we wouldn’t give up even half a meter of bicycle-lane width when we designed the bike lanes in New York City,” said Kim of WRI China, referring to the group’s refusal to widen proposed bike lanes in the US city to ensure that drivers would not be able to use them.

However, Beijing is not New York. The entire urban design is car-centric, from the width of the roads to the traffic light settings; pedestrian crossings are timed to cause drivers as little inconvenience as possible and the distances between footbridges are often lengthy, conveying the message that autos are the top priority and the needs of other road users are secondary considerations.

Moreover, the poor air quality and a lack of proper parking places for bicycles have resulted in residents becoming reluctant to cycle in the city, leaving the roads free for even more cars.

“The city of Beijing is at the first stage of Denmark’s ‘bikes-first’ development program, under which it has started to allow the numbers and facts to tell stories that will convince policymakers to instigate changes,” said the WRI’s Liu. “The next step for the Beijing government should be the realization that the focus has to shift away from cars and toward making cycling easy and making cyclists proud of their choice. That could be the future direction of more-sustainable development.”

Beijing’s road now. [Photo by Wang Zhuangfei/China Daily]

The challenged mindset

However, the preference for automobiles is firmly rooted in the minds of many Beijingers, revealing a choice that is more cultural and societal than economic.

Beijing was once the world’s bicycle capital, with the largest population of cyclists on the globe. Photographers were not slow to notice the extraordinary biking scenes on the city’s streets in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

“Every Chinese person of a certain age is interested in bikes, because we all grew up with them,” said Wang Wenlan, a well-known photographer for China Daily, who has been taking snaps of Chinese cyclists since the 1970s.

However, the relatively recent rise of the car has resulted in branding and cost becoming status symbols. That’s why Brunn, the German national, takes every opportunity to persuade people that cycling is cool, even for the wealthy. As cyclist and performer of bike tricks, she is one of a number of expats contributing to the revival of Beijing’s biking history, while helping to inspire an emerging generation of young, homegrown enthusiasts.

Shannon Bufton, owner of Serk, a racing-bike workshop and one of the co-founders of Smarter Than Car, a think tank for green city transportation, said the government should be praised for retaining its faith of cycling as a mode of transportation.

“Many years ago, the government could have just said, ‘Let’s just paint over the bike lanes and make them into parking spaces,’ but it didn’t because the government knew that in the future they would need all the bike lanes. The first step is to get more residents riding bikes to show the government ‘Hey, look, we want a better city; we want to ride bikes. So let’s do something to make the bike lanes better. Beijing has the best lanes for cyclists, and the refusal to abandon them all was a good gesture by the government. Now every individual should shoulder their own responsibilities and make their own efforts for the community.”

The growing number of eager young cyclists will be the key to the city’s transport revolution, according to Claudio Bebuzzi, a South African national and partner in Bamboo Bicycle Beijing, a do-it-yourself bike workshop. “Kids should be more proud of the transport they are using, the ways they are moving,” he said. “Around the world, in the past five or 10 years, I have seen that, in terms of a movement toward a more-sustainable transport system, nothing is better than riding a bike.”