.jpg)

Zhao Zhenying, (left), a 98-year-old nationalist veteran who fought against the Japanese, with Neal Gardner (center) and Yan Huan, who helped to bring Zhao’s story to light.[Photo/China Daily]

For Zhao Zhenying, from west Beijing, the second half of 2014 has been incredibly busy, perhaps a little too busy for a 98-year-old war veteran.

On July 7, Zhao was invited to attend a memorial ceremony at Lugou Bridge, often known as the Marco Polo Bridge, in Beijing’s southwestern suburbs, to meet with President Xi Jinping.

It was at the bridge 77 years ago that the Chinese Army fired the first shots against the Japanese Imperial Army and started the eight-year War against Japanese Aggression (1937-1945).

Just two months after his meeting with Xi, Zhao’s wheelchair was pushed into a room in a Beijing hotel, where he was confronted by legions of reporters armed with cameras and notepads. Just a short distance away at the Beijing Military Museum previously unseen photos, part of an exhibition exploring the cooperation between China and the United States during World War II, were attracting hordes of visitors.

“In the time between the memorial ceremony and the exhibition, we received a constant stream of interview requests from as far away as Hong Kong and Macao. I answered them all,” Ni Yingfeng, who has been Zhao’s career for two years, said. “The exhibition brought ever more calls than we could possible handle.”

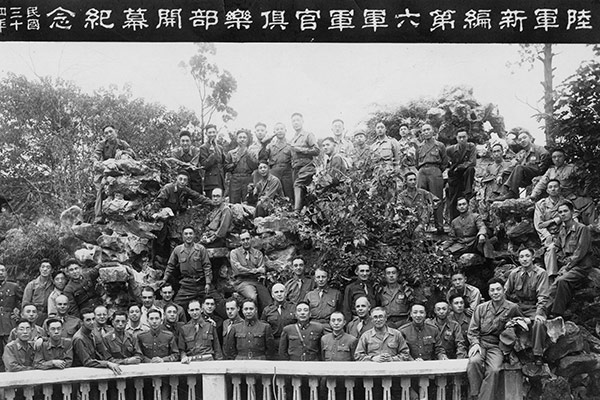

Major Zhao Zhenying with fellow Chinese and Allied officers of the New 6th Army in October, 1945.[Photo/China Daily]

Security chief

Small wonder. Between 1939 and 1945, Zhao was a soldier in the Chinese Nationalist Army, and fought the Japanese both at home and overseas. And when Japan officially surrendered to Chinese forces on September 9, 1945, Zhao, a battalion commander, was responsible for security at the ceremony in Nanjing.

However, all this attention would have been unimaginable on September 9, 2005, when a grand memorial was held at the Historical Archives of the Nanjing Military Command, whose main building was the site of the 1945 ceremony of surrender. Zhao wasn’t invited.

“No one had any idea about his existence,” said Yan Huan, who as the grandson of Pan Yukun, a prominent Nationalist general during the war, was among the guests.

“In retrospect, if there’s one person who should have been invited, it’s Mr. Zhao,” Yan said. “He saw everything with his own eyes-none of us did.”

Things soon took an unexpected turn. Yan, an architect-cum-amateur historian who found his late grandfather’s wartime history so intriguing he decided to write a book about it, unearthed crucial information in early 2006.

“During my online research for the book, I discovered a website set up by Neal Gardner in about 1999. Neal had photographed, scanned, and pasted all the souvenirs, papers, and photos brought back by his late father, John Gardner, a U.S. Army major, at the end of his two-year stint in what is known today as the China-Burma-Indian, or CBI, Theater of World War II. “My father came back in October 1945, and passed away on November 24, 1986 at the age of 73. I guess this is my way to remember him,” the 62-year-old wrote in an e-mail to China Daily.

Two items immediately attracted Yan’s attention-a small red diary that bore a number of Chinese signatures, and a photo of a group of US and Chinese officers, with the words “In Memory of the Opening of the New 6th Army Officers’ Club” printed in Chinese along its upper edge. “I immediately contacted Neal and asked for permission to paste the photos on a Chinese website,” Yan said. “Then, in the early spring of 2008, a man called from Beijing, saying his 92-year-old father has recognized himself in the photo on the website and had seen his own signature in the diary.

.jpg)

Major Zhao Zhenying with fellow Chinese and Allied officers of the New 6th Army in October, 1945.[Photo/China Daily]

Back from the dead

“How could it be possible? Weren’t they all dead?” Yan said. “However, I decided to give him the benefit of doubt and talked directly to the old man over the phone. His knowledge about my grandfather and the CBI Theater surprised me.”

Two month later, Yan left his home in Shenzhen, Guangdong province and visited Zhao at his apartment in Beijing. “We talked almost nonstop for two days, while all the pieces started to fall into place,” Yan said. “This man had been a battalion commander in the New 6th Army, and fought in the CBI between 1944 and 1945.

“He also told me his battalion had been in charge of security at the ceremony of surrender in Nanjing in September 1945,” he said.

When he heard that, Yan showed Zhao a file photo. “I don’t know who took it. But this image was probably the most widely distributed one about the event,” he said.

The photo showed seven Japanese representatives directly facing their Chinese counterparts, and behind them on the left edge of the picture, was a young Chinese officer wearing riding boots and white gloves.

“Zhao, who was seeing this photo, or any image of the surrender, for the first time since 1945, pored over it for a long while. Slowly, he pointing at the young officer and murmured to himself, ‘That was my position ...’,” Yan recalled. “He said nothing else, but it was more than enough to set me on the track.”

In May 2009, Neal Gardner, whose father fought as a member of the New 6th army, traveled from his home in Oklahoma to meet Zhao. Footage of their meeting shows the well-built US resident giving the frail old man a hearty embrace.

“This was a man who had known my father over 65 years earlier and I was making his acquaintance,” Gardner said. “It was like meeting a long lost relative. I cried out in delight and happiness.”

He presented Zhao with a CBI collar badge. The old soldier’s had been lost, or burned, during the turbulent years of the “cultural revolution” (1966-76), along with any other items that could bear witness to his personal history.

Unspoken history

“I fought the Japanese as a soldier of the Nationalist Army, under the then-Nationalist government. But then the civil war broke out between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists. With the triumph of the Communists and the founding of the People’s Republic of China, my veteran’s background suddenly became a potential landmine, something I would try anything to avoid,” said Zhao, who admitted he destroyed everything that could “incriminate” him. “For more than four decades, I had never talked to anyone about those experiences-not my neighbors, my children or my grandchildren.”

But memories are indestructible. On July 23, 1937, Zhao, a 20-year-old Beijing native, embarked a train and left his hometown. “White flags were hanging above the train (to indicate that the passengers were civilians, not military personnel), and as it crossed the Marco Polo Bridge, I pressed my face against the window and saw Japanese soldiers looking in our direction through their telescopes,” Zhao said. “Street battles were about to break out and Beijing was soon lost.”

Eventually, Zhao arrived in Jiangxi province in East China, where he trained at a branch of the Whampoa Military Academy, the country’s first modern military college. Between 1939 and early 1944, he was a member of the Nationalist Army and fought the Japanese in many parts of China.

“Then in March, 1944, our troops were flown to India,” he said, referring to his days in the CBI theater, where he met and befriended many Allied officers who had been sent to assist the Chinese army after the attack on Pearl Harbor in Dec 1941. Neal Gardner’s father was among their number. “They were mostly liaison officers, and since I spoke some English, it didn’t take long before we became close,” Zhao said. “While we were in Burma, I shared a tent with Daniel Pancake, a US army captain. It rained a lot and I still remember him chanting in his baritone voice: ‘Rain, rain, go away. Come again some other day ...’”

Days after meeting, Neal and Zhao traveled to Nanjing, the Chinese city most traumatized by the Japanese invasion.

On December 13, 1937, Japanese troops embarked on a six-week killing spree in Nanjing. More than 300,000 civilians and disarmed combatants died in what is now known as the Nanjing Massacre, or the Rape of Nanjing. The slaughter shocked the world, and made Nanjing the only real choice as the location for the ceremony of surrender at the end of the war.

“The job of maintaining order and security during the ceremony was given to our battalion to honor our performance during the war,” Zhao said. “All my accoutrements-the riding boots, trousers and gloves-were bought after our arrival in Nanjing. It was a moment that would live on in history, and we all knew it.

“To prevent an accidental discharge, our guns were not loaded. Although many people were present, including reporters and observers, I was the only person in the auditorium who was able to move freely,” he said.

John Gardner, then aged 31, was also in the hall, and he took a large number of photos to send home.

Later he wrote “The signing of the surrender terms took place on the ninth day of the ninth month at 9 o’clock. Also I left the States on the 9th of September 1943. This is my second anniversary oversees. Gee! I’m excited to get home,” he wrote in a letter to his family.

Gardner returned to the US a month later, but not before he had asked his Chinese friends from the CBI to sign his most cherished piece of memorabilia from the war, the little red diary. At the time, he would never have imagined that one day more than half a century later, the photos and the book would help an old man re-establish his identity.

“There are no words in the English or Chinese languages that can describe the feeling one receives when they can help brush aside the dust which covers the past,” Neal Gardner said.

Welcoming gifts

On the first page of the diaries that were given to the Allied officers as a “thank-you-and-welcome” gift from the Chinese army, were the words “Merry X’Mas” and “A Victorious New Year”.

Before arriving in Beijing to meet Zhao, Neal Gardner and Yan paid a visit to the Tengchong Guoshang Cemetery in Tengchong, Yunnan province, about 200 kilometers from the China-Myanmar border. The 52-square-meter plot was the site of a series of fierce battles between May and September 1944, as soldiers of the Chinese Expeditionary Forces retook Tengchong, the first town to be recovered from the Japanese army. More than 9,000 Chinese soldiers perished in the battle, along with 19 US Liaison Officers.

“As I felt the rainfall on my head, and as I felt myself get wet, I started to feel that maybe that was how my father had felt ...” Neal Gardner wrote, reflecting on his father’s experiences in the CBI.

On September 9, 2005, Yan joined the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Japanese surrender. Zhao watched a live television broadcast in his small apartment in Beijing, and as the historic footage appeared on the screen, he turned to his family and said, “I was there.”

Zhao Jingyi, his son, said: “He didn’t elaborate, and we all thought he was starting to lose his mind because of his age.”

In 2009, a year after Yan first met with Zhao, a friend who made documentaries went to the US National Archives in Washington to search for footage related to China during the war. “I asked him to keep an eye out for anything about the 1945 surrender ceremony, and he brought back some footage,” Yan said.

Later, he sat down with a few friends for a private viewing of the footage that had probably not been seen by any Chinese person since it was shot more than five decades before.

The film showed the moments immediately before the ceremony. The camera roamed across the exterior of the auditorium, showing the flags, the giant placard bearing the words “Victory and Peace” in Chinese, and the cars that carried the representatives along the heavily guarded boulevard to the front steps of the auditorium.

Then the camera zoomed in on individual soldiers. They were mostly shown in profile, smiling and making fun of each other. Suddenly, one turned and briefly looked directly into the lens. It was a 28-year-old Zhao, instantly recognizable by his large eyes and high cheekbones.

“The final piece of the puzzle had finally fallen into place,” Yan said.