A dispute in the self-proclaimed birthplace of Chinese rock climbing has resulted in devotees being banned from one of the region’s most famous, and important, sites, as Xin Dingding and Huo Yan report from Yangshuo, Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

Yangshuo, the only county in China with a mature climbing industry, owes its fame as climbers’ paradise to two visitors from the United States.

The first was former president Richard Nixon, who paid a visit to the scenic spot in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region during a visit to China in 1976. According to a tale found on many Yangshou-related tourist websites, Nixon was fascinated by a local feature called Moon Hill.

The 380-meter-high hill is named after a natural arch on the summit that resembles either a full or crescent moon, depending on the position from which it’s viewed. Nixon was immediately attracted, and asked his Chinese hosts a question that probably seemed logical in those Cold War days: was the arch, about 50 meters high and 50 meters in diameter, the result of the People’s Liberation Army firing a missile through the rock?

Although the former president was assured that the feature was entirely natural, he wanted to take a closer look so his hosts quickly cut a narrow path for him through the lush vegetation.

More than 15 years later, another visitor from the US, Todd Skinner, one of the world’s best-known free climbers, used the “Nixon path” to walk to Moon Hill.

According to the climbing guidebook for the area, “following his (Nixon’s) reconnaissance”, Skinner spent time in Yangshuo sometime between 1990 and 1993. It’s unclear how long Skinner stayed, but he is known to have used the “Nixon path” to approach the arch, where he established five routes, including one with a second pitch graded as “5.12d”, which was “the upper-limit for climbers at the time”, according to Zhang Yong, deputy director of the Yangshuo Rock Climbing Association.

Skinner, who died in a climbing accident in 2006, wasn’t the first climber on the local hills, though. Germans Wolfgang Gullich and Kurt Albert and Austrians Heinz Zak and Ingrid Reitenspies explored the local rock faces in the 1980s, according to Adventure magazine, but Skinner is the person the locals credit with starting the climbing boom. “In our minds, Todd Skinner is the person who created Yangshuo’s climbing history, and Moon Hill is the birthplace of climbing in Yangshuo,” Zhang said.

“He (Skinner) showed people the beauty of climbing in Yangshuo, and laid the foundations for the county to become a paradise for climbing in Asia,” he said.

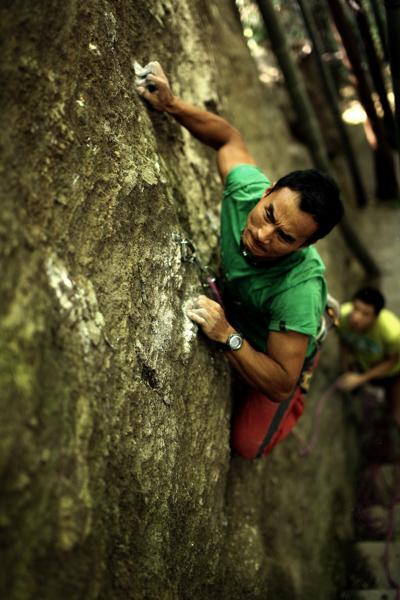

Zhang Yong climbs a face on Laoshan Mountain in Qingdao, Shandong province, in 2013.[Photo by Zhao Si/China Daily]

On the way up

More than 20 years later, there are few records of Skinner’s days in Yangshuo-no photos, no written evidence-but his arrival undoubtedly changed the fate of the small county.

“For a climber, the only way to rise through the ranks is to practice and complete routes of progressively higher grades,” Zhang said.

After Skinner created the routes, other foreign climbers flocked to the area to attempt them, leading to the county becoming increasing famous overseas while remaining virtually unknown to the small number of homegrown climbers.

Ding Xianghua, former head of the Chinese Mountaineering Association’s Rock Climbing Department and a pioneer of Chinese climbing, said he first learned about Yangshou’s potential in 1999, when friends from overseas mentioned it.

“In Beijing, we mostly practiced on the natural crags in Miyun county. Yangshuo was better known to us as a tourist spot, not a climbing destination,” he said.

After recommendations from climbers from Hong Kong and foreigners in Beijing, Ding and seven other enthusiasts spent a week in Yangshuo during the 1999 Spring Festival.

“From a professional perspective, Yangshuo has many advantages. There are abundant natural crags and Karst towers everywhere. The crags have the angles that all climbers desire, and the rock surfaces are clean, but also uneven, with cracks that provide plenty of handholds,” he said.

The natural advantages attracted foreign climbers, some of whom settled in the area and helped to develop the burgeoning climbing industry.

Zhang, of the Yangshuo Rock Climbing Association, recalled Paul Collis, a British engineer who lived in Hong Kong. Collis came to Yangshuo in 2004, the same year Zhang quit his bar job in Hezhou, Guangxi, and moved to Yangshuo.

“Every month, he came to Yangshuo to open many new routes. He edited and printed a climbing guidebook in English to let people around the world know about Yangshuo,” Zhang said.

Collis edited the guidebook until 2009, when he handed the job over to Chinese climber Qiu Jiang and Tyson Wallace from the United States. Some of the money earned from book sales is used to open new routes and maintain existing ones.

Many Chinese climbers are unable to afford the expensive equipment-primarily bolts, carabiners and rope-that are needed in large quantities when establishing new routes. Collis used his experience as an engineer to break down, then reassemble old molds and make replacement equipment. “That enabled us to open a lot of routes,” Zhang said.

The number of routes has risen from 20-plus in 1999 to around 1,000, thanks to the efforts of climbers from home and abroad. In the guidebook, every route is marked with the names of the climbers, many of them from overseas, who created them.

Local Knowledge

Ding, who headed the CMA’s climbing department for 16 years, said China has several climbing centers-including Miyun and Fangshan counties in Beijing, Ziyungetu in Guizhou province, Xinxiang in Henan province, and Kunming in Yunnan province-but Yangshuo is the only one with a fully developed climbing industry and a lot of local support.

Zhang underscored that view: “When you ask a farmer around here what climbing is, they can tell you. But if you ask the same question in Northeast China, the locals won’t know.”

Sadly, that local knowledge has occasionally led to friction. When the villagers saw the revenue local climbing clubs were generating on the barren rock faces, some of them decided they wanted a slice of the action.

In 2010, some tenant farmers began charging climbers for passage across their land. However, many climbers were unwilling to pay, which resulted in heated arguments and sometimes even physical violence. Some people threatened to cut the climbers’ ropes or impound their equipment, bags or bikes. Eventually, the local authorities advised climbers to pay the farmers to avoid potential flashpoints.

Liu Yongbang, a top-flight Chinese climber who runs his own club, said he pays villagers when he organizes commercial activities in their area. “But there are more problems than that. Every year they ask a higher price, although we’re just passing through their land,” he said, adding that he has appealed unsuccessfully to the government to make a ruling on the issue.

“The government won’t speak up for us. It doesn’t object to us climbing, but it doesn’t support us, either. After all, the climbing industry can’t generate as much revenue as tourism. There’s a big difference between the millions of tourists who visit Yangshuo, and the thousands of climbers who come here,” he said. “Also, the government thinks climbing is dangerous and could cause problems. We have to solve the problem by ourselves, and open more new routes on new sites,” he said.

The classic routes on Moon Hill, the cradle of Yangshuo’s climbing industry, can never be replaced, though.

In 2013, a private company that has rented the hill and surrounding land banned climbing, citing the potential for fatal accidents.

Some enthusiasts simply ignore the ban, though, and last year, Zhang and some friends proposed replacing the aging bolts and carabiners fixed to Skinner’s five classic routes, because the original equipment is badly worn and could pose a threat to the illegal climbers.

The group raised funds and spent more than 10,000 yuan ($1,600) on equipment. Armed with approval documents issued by the local government, Zhang and his team refurbished the equipment on two of the original routes.

“Later, we discovered that the new carabiners had been smashed by the company to stop people climbing, and we were forbidden to replace the equipment on the three other routes,” he said.

He asked the county government to arbitrate on the matter, but the officials told him to negotiate with the company and solve the problem himself.

“Moon Hill was a place for climbing 23 years ago, long before it became a scenic spot. It’s the birthplace of Chinese rock climbing and has five classic routes created by a legend. But now, climbing and other ‘dangerous’ outdoor activities have been banned. It’s a really sad turn of events,” he said.